Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

As the metagame continues to settle after the unbans of Jace, the Mind Sculptor and Bloodbraid Elf, an interesting dichotomy has arisen: some players claim that the presence of these powerful four-drops has made the format faster and less interactive, while another sector espouses the opposite belief. I took it upon myself to find out which camp has a better read on Modern.

The former group claims that a deck lacking both Jace and the Elf cannot hope to win a grindy, fair game, and must thus resort to trying to get under decks with the cards. The latter holds that because these cards have mostly boosted the fortunes of fair decks, the format is more interactive than it has been in recent memory, resulting in longer, slower games of Magic.

This article lays out the current slate of top decks, then compares it to that of the most recent lineup before the unbans. Next, it attempts to determine whether the most represented decks attempt to win faster than their predecessors did.

The Usual Suspects

In order to establish a frame of reference, we have to establish a baseline of what decks are the most common performers in the current environment. While Wizards' change in policy regarding the publication of Magic Online league data has made direct comparisons with the past somewhat difficult, I think it's reasonable to assume that decks that make their way to the 5-0 listings regularly are at least somewhat well-positioned. With that in mind, a results accumulation resource like MTGGoldfish should still provide a sufficient approximation of what decks to focus on.

Another useful exercise at this stage is to establish a given deck's degree of interactivity. Storm isn't operating on the same axis as Jund, and there are plenty of decks somewhere in between those two that need their place defined. For the purposes of this discussion, we'll use the following categories.

Another useful exercise at this stage is to establish a given deck's degree of interactivity. Storm isn't operating on the same axis as Jund, and there are plenty of decks somewhere in between those two that need their place defined. For the purposes of this discussion, we'll use the following categories.

Minimally interactive - These decks pack few or no ways to directly interact with their opponents. Some of their action cards can interact, but the gameplan is mostly to ignore what the opponent is doing.

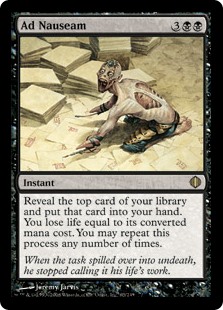

Examples: Ad Nauseam, Gifts Storm

Moderately interactive - These decks tend to have a firmly established gameplan, but are also capable of disrupting opponents if the situation dictates it. The disruption these decks employ is often integrated into their gameplan.

Examples: Hollow One, Humans

Highly interactive - Disrupt early and often is the name of the game here. These decks generally have a small handful of win conditions, and then dedicate the rest of their shell to ensuring that opponents must fight tooth-and-nail to execute their own gameplans.

Examples: Jeskai Control, Mardu Pyromancer

The Need for Speed

Last but not least, we have to talk about speed, or proactivity. Decks like Burn aim to win as fast as possible; on the other side of the coin, control decks want to establish themselves on the battlefield and the stack, and then win much later. Here are some broad categories we can use to categorize the speed of the decks we are interested in evaluating:

Fast decks - These are generally looking to win by turn four. Some of them are even capable of finishing the game before then if left to their own devices.

Fast decks - These are generally looking to win by turn four. Some of them are even capable of finishing the game before then if left to their own devices.

Moderately fast decks - These decks are generally proactive and looking to win the game in a reasonable time frame, but are not quite as "all-in" as the fast decks. Provided they draw the proper tools, these decks are as comfortable winning the game on turn four or five as they are on turn 10.

Examples: Grixis Shadow, RG Ponza

Slow decks - These decks have piles of interaction and a nominal amount of win conditions. Their goal is usually to stymie the opponent's gameplan, eventually find their ways to win, and then close the game out at their leisure.

Examples: UW Control, Lantern Control

Measuring Up

With these categories in mind, let's take a look at the top 15 decks currently on MTGGoldfish and see where things stand in the pre- and post-unban metagames.

My prediction prior to putting these lists together was that the average speed and interactivity of a deck in the metagame will not have changed much, but the metagame will have become more polarized. Fast, minimally interactive decks and slow, highly interactive decks would find themselves on the rise, with the middle ground between these extremes eroding to some degree.

The hypothesis ended up only half-right. A look at the high-ranking decks in a vacuum instead favors the view that the metagame has gotten faster; while most of the decks here are interactive to some degree, they are all looking to win quickly. Cards like Bloodbraid Elf have injected speed into the likes of Jund and RG Ponza. Uxx control decks seem to be the only representatives of the slower side of the spectrum that are performing at a high level, as prison strategies like Lantern Control are pushed out by the re-emergence of decks heavy on artifact hate.

The hypothesis ended up only half-right. A look at the high-ranking decks in a vacuum instead favors the view that the metagame has gotten faster; while most of the decks here are interactive to some degree, they are all looking to win quickly. Cards like Bloodbraid Elf have injected speed into the likes of Jund and RG Ponza. Uxx control decks seem to be the only representatives of the slower side of the spectrum that are performing at a high level, as prison strategies like Lantern Control are pushed out by the re-emergence of decks heavy on artifact hate.

However, we cannot definitively state that the meta has gotten faster until we take a look at a snapshot of the metagame prior to the Jace and Bloodbraid unban:

This list of decks does confirm the assertion that the current metagame has gotten faster and less interactive. Not only are there more representatives for the decks I consider fast (five examplars now to three previously), there's also a dip in decks that could be thought of as highly interactive (we went from seven decks in that ledger to four). Given this information, it's reasonable to conclude that one of the major ways decks have adapted to the rise of Bloodbraid and Jace is to speed up and duck under them.

Drilling Deeper

While our categorization does a reasonable job of illustrating broad trends in the metagame, we can also narrow our focus by examining the decklists of various archetypes one might expect to see in each metagame and how they have changed.

Let's begin the comparison with one of the pillars of Modern: BGx Rock. This is an Abzan list from just before the unban announcement.

Abzan, by ef_apostrophe (6-1, MTGO Modern Challenge #11145571)

Compare this Abzan list to a Jund one from the latest MTGO Competitive League list dump.

Jund, by cliang (5-0, MTGO Competitive League)

Jund has classically been considered to be a more aggressive deck than Abzan, and a look at these two lists illustrates why very well: its removal spells can double as reach, its manlands are more offensively slanted, and Dark Confidant provides a strong impetus for closing out games before its drawback kills its controller. As Jund is currently ascendant, players can expect more offensive pop when opponents open with Swamp into Thoughtseize.

Next, let's look at some of the more aggressive decks. Here's the Bogles list Dmitriy Butakov piloted to a win in this year's Magic Online World Championship.

Bogles, by Dmitriy Butakov (1st Place, Magic Online World Championship)

Bogles was fringe at best in the recent past, but now it's back with a vengeance, and one of the big reasons why is that it demands a very specific type of interaction. Spot removal spells are often useless, while black discard spells and sacrifice effects can be shut off with Leyline of Sanctity. Countermagic or enchantment destruction still stops Bogles, but only when paired with a clock, or the Bogles player will eventually draw through such disruption.

Compare this deck to a fast one from the previous metagame, Counters Company.

"Counters Company, by Steve Campen (1st Place, SCG IQ Bernardsville)

Bogles is built with the idea of invalidating spot removal in mind, whereas Counters Company's combo finishes are highly vulnerable to that very type of card. Furthermore, the toolbox nature of Company decks allows room for a few cards that push a plan other than the combo (such as Fiend Hunter, Tireless Tracker, Tidehollow Sculler, and Voice of Resurgence), but the all-in nature of a deck like Bogles does without such luxuries; virtually every inclusion in that deck is either part of the primary gameplan, or protects the primary gameplan.

These differences are only part of why Company is in the outhouse while Bogles is in the penthouse. More importantly, they establish a clear trend reinforced by the uptick in decks with recurring threats like Hollow One's Flamewake Phoenix and Bloodghast, or redundant proaction like Burn's removal-proof reach. Bloodbraid Elf and Jace, the Mind Sculptor have indeed primarily boosted slower decks, and the field has adjusted by rewarding decks that complicate interacting.

These differences are only part of why Company is in the outhouse while Bogles is in the penthouse. More importantly, they establish a clear trend reinforced by the uptick in decks with recurring threats like Hollow One's Flamewake Phoenix and Bloodghast, or redundant proaction like Burn's removal-proof reach. Bloodbraid Elf and Jace, the Mind Sculptor have indeed primarily boosted slower decks, and the field has adjusted by rewarding decks that complicate interacting.

Running Off

Changes in the highest echelons of the metagame are increasingly apparent. But whether these development are good, bad, or neutral for format health and diversity remains to be seen. If you have any opinions on the current state of the format, or on the analyses I performed to arrive at my conclusions, drop me a line in the comments.

Interesting topic for discussion and I appreciate your style.

Anecdotally I’ve found things to be about half a turn slower on average since the unban. I’d put this down to a general uptick in midrange strategies overall, as death’s shadow has generally been supplanted by jund.

Remember, abzan wasn’t anything but a fringe player in the death’s shadow world, so by making the comparison above (abzan to jund) you may have been comparing the wrong decks.

I’ve also locally seen quite a few people move away from their infect, burn and bogles decks towards stuff like Affinity, jund and *insert jace deck here*. This switcharoo has definitely meant a local slowdown in the modern meta.

Also decks like KCI which are having a bit of a Renaissance are only really able to crop up when the format sees a temporary slowdown (which does happen occasionally as a natural part of the meta swinging back and forth like a pendulum or a wave)

It’s definitely possible that this happens at the local level; in fact, I’d expect it to be the case in some locales. If folks were on interactive decks before the unban, they now have stronger options, which will prompt them to double down and push opponents to play decks that aren’t as soft to them. If we had looked at this chart a couple of weeks ago, I suspect we’d have come up with a different answer than we did today; this is in part because the inclusion of MTGO data slants us toward aggro as compared to a purely paper-centric look, and also because MTGO tends to iterate very quickly, and you can expect a reasonable amount of settling in the metagame by the 2-month mark (which we are approaching).

I see what you’re saying regarding the Abzan vs. Jund comparison, but the Death’s Shadow vs. Jund comparison doesn’t work as cleanly because Shadow is still around and doing well (though not quite as well as it did before the unban). That strategy is clearly viable, and not going anywhere. Abzan, on the other hand, has basically dropped off the face of the earth. I also attribute KCI’s resurgence to the card pool for the deck improving; a deck that didn’t function unless it drew certain cards got 4 more effective copies of them in Whir of Invention. I suspect didn’t see as much of it before now because graveyard hate was in high fashion until recently thanks to midrange and control becoming increasingly graveyard-dependent, and because Lantern was a powerful option with very similar cards and not much of the combo-oriented fragility.

Just FYI none of the versions of kci which have placed well in tournaments recently have been running whir of invention. Other than that, sure. =)

Interesting. I saw the Whir version and I guess I just thought everyone would be on it. I guess I thought wrong.

Your axis of interactivity is fine but speed seems really arbitrary – the spectrum of moderately fast being “winning turn four to ten” frankly just covers every deck in the format besides lantern and turns and maybe the grindiest of control decks. So it might as well be binary.

Also if im not mistaken you weight the fifteen decks equally? We could have seven fast decks representing just twenyy percent of the top fifteen archetypes – you cant just say the format is faster because now nine of fifteen are fast when it used to be seven – the percentage share is extremely important. I get that its a crude sample or limited data – but this sort of conclusion is borderline meaningless,

I can agree with the criticism on the speed axis; I probably should have given that scale a bit more granularity, as it is kind of odd to have Humans lumped in with Jund and Eldrazi Tron (it is clearly faster than they are). I also toyed with the option of weighting the entries, but I’d be pulling the weights out of thin air; none of the online metagame data is really trustworthy for this purpose. I know that weighing them equally isn’t ideal, but it seemed like less of a problem that slanting things one way or the other and making it more subjective.

I will push back on these problems invalidating the conclusions, though. I decided to go back and assign numbers from 1-5 on the speed axis (with the likes of Affinity earning a 1 and Lantern being a 5), and re-evaluated the lists. Here’s what I came up with:

Current metagame:

4x 1s (Affinity, Bogles, Gifts Storm, Hollow One)

5x 2s (Ad Nauseam, Burn, Dredge, Grixis Shadow, Humans)

4x 3s (Eldrazi Tron, Gx Tron, Jund, Ponza)

2x 4s (Jeskai Control, UW Control)

Average rating: 34/15 = 2.27

Previous metagame:

3x 1s (Affinity, Counters Company, Gifts Storm)

4x 2s (Burn, Dredge, Grixis Shadow, Humans)

5x 3s (Abzan, Eldrazi Tron, Gx Tron, Madcap Moon, Titanshift)

3x 4s (Jeskai Control, Mardu Pyromancer, UW Control)

Average rating: 38/15 = 2.53

Not a massive shift, but one that is at least somewhat noticeable. I think my conclusion holds.

I think there’s more to this than just the issue of a sliding scale for speed. Defining what constitutes a “win” is critical, since decks like lantern and Tron are much, much faster than jund, but you consistently refer to lantern as a slow deck (a 5? Seriously?). That seems irreconcilable with the free win nature of turn 3 Bridge – similarly a turn 3 Karn is a much faster win than pretty much any humans draw, on par with the fastest affinity or storm kill. It may not affect your current analysis, but likely should be addressed at some point. Is the length of time a game lasts indicative of the deck’s speed? Or of the opponent’s stubbornness? You just have to look at game 1 of the most recent PT finals to see how silly that would be as a benchmark.