Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

Everyone’s heard of the famous quote, “…in this world, nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” In the Magic community, I’d like to put forth a third certainty: controversy. It seems like no matter what WOTC does, somebody somewhere is going to be offended, upset, and spark drama on social media.

Last week was no exception.

It all started with an allegedly leaked image depicting a Buy-a-Box promo Flusterstorm for the upcoming release of Modern Horizons. The image made it to social media, where major Magic personalities made it widely available to the public.

That’s when the controversy erupted. In various forms of written critique, “MTG finance” was blamed for the leak, blamed for its dissemination, and blamed for the resulting spike in Flusterstorms price.

Some folks piled on, while others came to MTG finance’s defense. Take a look at the numbers of retweets, likes, and replies. Everyone has an opinion on such heated topics. If you have some time, check out the responses to these tweets, linked below. The sentiment from the community is eye-opening.

Obviously, I won’t be able to convince an entire community of one side or another in a single article. But I hope to convey a couple of important points that both sides should consider when entering into a debate on the merits/pitfalls of MTG finance. I’ll try to be as unbiased as possible, but please keep in mind this is an MTG finance website.

Point 1: Magic is Founded on “Finance”

Ever since Richard Garfield invented the game and designed it with rarities, there became a financial component to Magic. There were 16,000 copies printed of each Alpha common and only 1,100 of each rare—hence, from day one rares were fifteen times harder to come by than commons. In fact, if you look at the patent filing for Magic, it explicitly states:

“The game further includes the unique feature of components that have a tradable and a collectable status. In other words, a certain amount of the game components have a limited availability to the players, thus, increasing the value of the components and encouraging players to trade and collect game components.”

In plain black and white, Richard Garfield states the importance of cards having rarity and value to the game. If variable card values are not to one’s liking, they probably shouldn’t engage in a game built upon such an economy. In the background section of the patent, there’s an explanation of the importance of this economy:

“Trading cards are typically exchanged among enthusiasts to obtain cards that are needed to complete a set of related cards or to collect cards that are not readily available. Collectors buy and sell these cards for their economic and historic value. The cards themselves have varying monetary values, depending on the popularity of the individual depicted thereon and the availability of each card, some being more common than others. Such cards are typically sold through retail game stores and other specialty outlets.

Playing cards, on the other hand, especially the well-known fifty-two deck face cards, are easily and readily available. The cards themselves, individually and collectively, generally have no value other than for amusement. Many different games can be played with a single deck of playing cards, limited generally by the imagination of the players. Some card games require cards especially printed for that game, and these cards have little value outside the playing of that particular game.”

I’m not a lawyer, but it’s fair to say that removing the financial aspect of Magic would mean this game would not look anything like it does today. At least, the patent would have to use different phrasing. For those who detest the fact that cards have varying rarities and can be traded with monetary value are dissenting against one of the purest components of the game itself.

It’s a regular Catch 22. The game exists because of its economy, yet people hate the economy of the game.

Point 2: Magic Prices Have Increased Well Before MTG Finance

It’s difficult to pinpoint the beginning of “MTG finance”. People have probably been trading with the intent of increasing their collection’s value since the game’s invention in 1993. I personally attribute the origins of the “MTG finance” community back to Jonathan Medina’s articles on StarCityGames.com. He began his series on August 11th, 2010, covering a range of financial topics.

Even earlier, Kelly Reid founded this website on the basic premise of “helping readers get more out of their collection.” Quiet Speculation’s first published article dates back to May 17th, 2009, over a year before Star City Games picked up Medina. If we use this as the birth of “MTG finance”, then the community just celebrated its tenth birthday.

What was the financial landscape of Magic like before 2009? Did card prices remain largely stagnant, with only Standard (and Extended) rotation driving costs? Absolutely not! It turns out card prices were appreciating well before the founders of MTG finance hit the scene. In fact, I can track such price increases throughout time by examining them in old issues of InQuest magazine.

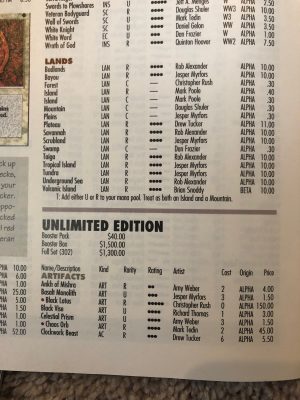

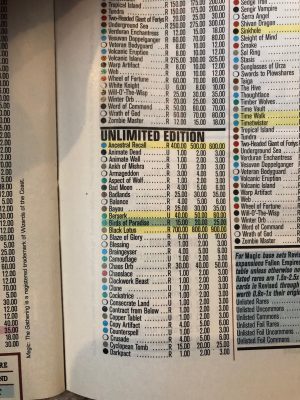

For argument’s sake, let’s take a look at the price of some Beta Duals and Unlimited Black Lotus from InQuest’s first and last issues. These prices will be least impacted by random fluctuation in Standard, metagame shifts, etc.

InQuest’s first issue from May 1995 shows that Unlimited Black Lotus’s value was around $150. Beta Underground Sea was $10. Fast-forward to issue 150, published in October 2007 (still before Quiet Speculation and Jonathan Medina hit the scene), and you see a very different story. Unlimited Black Lotus is worth around $800 and Beta Underground Sea is $275.

With this data in hand, I’d maintain the point that Magic’s collectability and success were responsible for these massive moves in price between 1995 and 2007. It stands to reason that further appreciation should be expected to happen as Magic’s popularity grew even further between 2007 and 2009.

Black Lotus appreciated 433% from 1995 to 2007. If we extrapolate this rate of return for the next 12 years, 2007 through 2019, we would have predicted a Black Lotus price tag of around $3500. Instead, it’s around $10,000. You could make the argument that the delta between $3,500 and $10,000 is the result of a self-serving MTG finance community. But we all know past performance never guarantees future returns. It’s difficult to say what Black Lotus would be worth today if there was no “MTG finance” but I’d argue it would be at least $3500 because Magic’s growth through the past decade has been huge.

Point 3: Supply & Demand vs. MTG Finance

On Wall Street, the stock market will often overshoot to the upside and downside through never-ending fluctuation. A bout of bad news will emerge and people sell their holdings out of panic, thus degrading prices excessively. Then there’s a streak of good news and stock prices overheat, trading well above fair value. It’s possible to take advantage of these oscillations, buying when the panic peaks and selling when euphoria takes hold.

The short term over- and under-shooting of fair market value is related to speculator emotions, hype-driven writing, and the “Stock Market Finance” community. This community can create short term impacts on individual stocks, but in the long-run supply and demand should dictate that stock’s fair value.

In the same way, Magic card prices can spike or tank in response to community influence. The most recent example would be Flusterstorm, which doubled overnight once the alleged leaks surfaced. Speculators likely shopped around and purchased multiple copies at the old price in anticipation of increased demand.

You can point blame at this community for the short term impact on price—I agree that speculators likely bought out the market, causing the card’s value to increase rapidly. These same “MTG finance” people will try to establish a new, higher price point by listing their newly acquired copies at 2x the old price. In the short term, this stranglehold on supply, combined with hype and emotions, will cause the price to spike.

Over a longer period of time, however, Flusterstorm’s price will not be set by these speculators. Speculators have no interest in owning 20 copies of Flusterstorm—their goal is to make money. They only make a profit when they sell. They can list these cards at whatever silly price they want; if no one buys, then they’ll drop their price. Others will enter the market too, undercutting each other to try and get a piece of the action. In the end, the price will drop until players are willing to pay the listed price, and copies will once again exchange hands.

Thus, Adam Smith’s Invisible Hand will guide Flusterstorm to its new price point. MTG finance can be a nuisance and create price spikes in the short term. But in the long term, the economics of supply and demand are what establishes a card’s price. In the extreme case, when a concentrated few speculators control a majority position of a card, they may control the price. In that case, buyers simply won’t pay up and no copies will exchange hands.

This is unfortunate because it prevents some people from obtaining the cards they want. The good news is this is only really possible with Magic’s rarest and oldest cards, which aren’t played by 99.9% of the player base. This could also apply with something like a Masterpiece card, which has much more affordable counterparts that perform the same function in a deck.

Wrapping It Up

“MTG finance” has been around for a decade. But card prices, trading for value, and rarity are inherent to Magic’s design. Richard Garfield recognized this and included these details in his patent for the game. Without a Magic economy, there is no Magic. It’s that plain and simple.

That said, I will concede the fact that Magic card prices are manipulated by an “MTG finance” community, at least in the short term. This community buys out the market of a card in response to emotions and news, such as an alleged leak from a new set. The key though, is that this community doesn’t make a dime on such behavior unless the market is willing to bear a higher price point. If no one is willing to pay up for Flusterstorm at $30, then sellers will drop their price to $28. Then $26.

Sellers will continue to do so until a sale is made. At that point, the most a single buyer is willing to pay for the card becomes the new price for the card. Adam Smith predicts this will happen via the Invisible Hand that adjusts the price until exchanges are made. In the long run, as long as people behave rationally, a card will find its final price no matter what path it takes.

We can look at Flusterstorm’s spike and blame MTG finance. But if you want to point blame for the card’s new, higher price, then you need to point at Richard Garfield, Wizards of the Coast, and the person buying Flusterstorm at the higher price point. They’re the ones who make Magic’s long-term economy what it is.

…

Sigbits

- Mox Diamonds buy price on Card Kingdom’s site hit a recent high, $175. This reflects a gradually draining supply on TCGPlayer, and it wouldn’t surprise me to see the buylist hit $200 if Card Kingdom gets desperate enough to restock. There’s no manipulation or “MTG finance” here—this is just a popular card on the Reserved List with sustained demand.

- The Worldwake printing of Jace, the Mind Sculptor used to have the highest buy price on Card Kingdom’s site. But now the Eternal Masters printing is sporting a $100 buy price. I suspect each nonfoil printing is worth about the same, and Card Kingdom places the highest buy price on whatever version they have fewest copies of at any given moment.

- The buy price on Grim Monolith hit a new high lately—Card Kingdom has it on their hotlist with a $95 buy price. This is yet another popular Reserved List card that is likely to climb higher over time as copies on the open market dwindle.