Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

Because I view Magic cards as a viable alternative investment vehicle, I often compare it to other investment options. In the past, I’ve compared various parts of Magic with comic books, artwork, vintage video games, and of course the stock market.

The stock market comparison runs deeply, with many parallels (up to and including websites that track prices on a chart). However, a recent Twitter conversation with Jarrod Ator (@jarrodator) has helped me recognize multiple contrasts. It turns out, some of the similarities I’ve perceived are somewhat misleading. This week I want to share key takeaways from our conversation and offer some words of caution when comparing Magic to stocks.

Difference 1: How “Price” is Defined

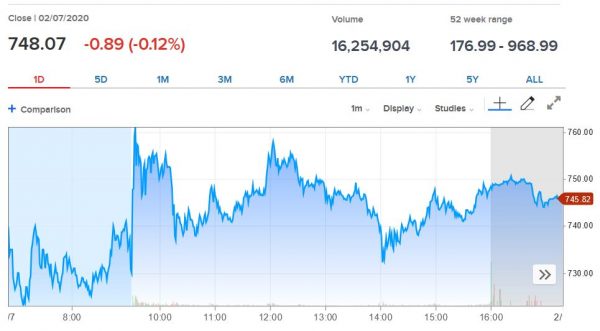

The first difference I want to highlight is easiest conveyed with an example. Let’s say I asked readers to research and identify the current price for Tesla stock (symbol: TSLA). The exercise is trivial—I typed TSLA into CNBC, Yahoo Finance, and Google and obtained the identical answer in each case: $748.07 at the close of February 7th, 2020.

Now I ask a similar question about Magic: what is a near mint Mox Diamond worth? Just like before, I checked three popular sites for pricing. Here’s what I found:

Card Kingdom: $289.99 (sold out of NM, they had EX in stock at $260.99)

Channel Fireball: Sold out of NM, no pricing provided. They had SP in stock at $249.99

TCGPlayer: Cheapest LP is $223.50, cheapest NM is $254.99

Three different stores with three different prices. If different stock brokers used different prices for their stocks, what would happen? The broker with the cheapest shares would have theirs sell first, within moments, and then the next cheapest shares would sell, and so on.

Granted when I researched Tesla’s stock price, I wasn’t checking brokers individually. But we can be confident the price differential between brokers would be no more than a couple pennies (and that difference would constantly evaporate).

This example captures the first major difference between Magic and stocks: pricing research is inconsistent. Every stock price can be researched with utmost precision, and every stock price reflects the last transaction. Therefore, a stock’s “price” on CNBC or Yahoo Finance reflects the most recent price someone bought at and someone sold at.

When researching a card’s price, all we have is a list of seller’s asking prices. This is reflected as “TCG low”, or Card Kingdom pricing, or MKM pricing, etc. We use the lowest asking price to establish a card’s value, rather than the last sold price. This allows for the price manipulation we’re used to seeing during buyouts. Just because people suddenly demand 10x for the same card doesn’t mean it’s actually worth that much more.

On the other hand, if a stock’s price jumps significantly, it means people have truly bought the stock at the higher price (at least momentarily).

If all shareholders of the stock above (Telenav Inc) decided they didn’t want to sell their shares for less than $6 anymore, they all could have raised their sell price. But the price on CNBC and other websites would only reflect a higher value if shares actually exchanged hands at that higher price.

Thus, there’s a dramatic difference between a quoted stock price and a quoted Magic card price with profound implications on how people interpret the market.

Volume Volume Volume

Keen scrutinizers of the previous section may challenge me on one comment I made regarding completed transactions. Technically, thanks to eBay, we can explore recently sold listings to help establish pricing in a way that mimics the stock market.

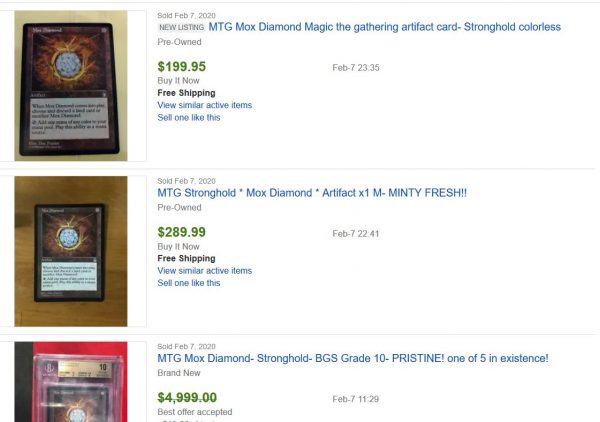

But how useful is eBay’s data, really? Take a look at the last three sold listings for Mox Diamond and tell me what it’s worth…

The top listing sold for $200, well below “market price”. The middle listing sold for $290, more than major vendors are even asking for a nice copy. And the third listing sold for who-knows how much, given its grade.

In total, I counted around 20 completed listings thus far for the month of February, with pricing and condition all over the place. This data could be a helpful guide in determining a card’s price, but it’s far too incomplete to be a definitive source. What’s more, this only reflects the cards sold on one website, and likely captures only a small fraction of the monthly volume of transactions.

What fraction is it? We have no clue! That’s the second fundamental difference between the stock market and the Magic market. Let’s rewind back to that Tesla stock chart I showed for February 7th.

The number above the chart, under “Volume”, indicates how many shares exchanged hands throughout that day. There are two things I want to point out with that number. First, notice how precise it is: 16,254,904. This is not to be confused with 16,254,903 or 16,254,905. No rounding here, folks, this is the exact number of shares to exchange hands.

Second, understand the sheer volume of shares exchanged in a single day. At $750 a share, that’s over $12 billion in transacted dollars in one day! This highlights the magnitude of the stock market as well as the liquidity. Compare that to the 20 Mox Diamonds that sold on eBay for an average of roughly $250, or $5000 in “liquidity”. Just a few orders of magnitude less, right?

This key difference has far-reaching implications. The larger market cap and volume offered by stocks supports my thesis that scaling in stocks is far easier. For example, someone could purchase $1 million worth of a single stock without having much impact on the overall market. It would be a momentary blip. But spending this much money on a Magic card is impractical at best. Imagine purchasing $1 million in Mox Diamonds—you would 50 copies in and suddenly the price would be 30% higher. After 200 copies, you may have bought out most of the internet!

The low volume of Magic becomes even more problematic when dealing in rarer cards. Looking up the value of Alpha Wheel of Fortune, for example, is no easy task. Besides the heavy dependence on condition, the “last sold” transaction may or may not be all that useful in determining current value. Without much volume, only seller asking prices can be used to estimate value—this, of course, biases cards to reflect higher prices.

Store buylists are one way of reviewing “bids” for the card, but they’re often biased far lower so the vendors can turn a profit. There’s no website where individuals can post what they’re willing to pay on various cards to create a reliable “bid” to compare with the “ask” prices we’re used to. In theory, such bids exist because players and collectors are always wanting to get various cards at the right price. But lack of transparent information creates a deep divide between valuing stocks and valuing Magic cards.

Wrapping It Up

Investing in Magic cards is rather straightforward. By now most serious buyers know the right places to park their resources—Power, Duals, highly graded Alpha and Beta cards, Reserved List, etc. These assets have provided spectacular returns over the past 25 years, often outperforming the stock market.

However, just because we can compare returns between Magic cards and stocks doesn’t mean the two are exact parallels. In fact, there are many profound differences between the two markets that have far-reaching implications. Recent Twitter discussions with Jarrod Ator inspired me to think about these implications more deeply.

Two of the most critical differences revolve around the lack of information available in the Magic market. First, the value of stocks involve the “last traded” price while the value of Magic cards typically uses seller asking prices only. And second, there isn’t volume information on Magic cards outside of eBay completed listings, which can be convoluted and misleading.

These two factors create an environment in Magic that leads to things like arbitrage, price manipulation, and temporary buyouts. Such pitfalls must be avoided to profitably invest in Magic. And there are others.

This topic has broad reach and can touch on even more differences between these and other markets. Next week, I hope to expand this into a series of at least two parts, where I explore even more of these differences and explain how they make Magic a unique market for investing. If you liked this week’s topic, stay tuned for more next week!

…

Sigbits

- It’s no coincidence that I mentioned Mox Diamond as one of the examples of this article. That artifact has been climbing in price lately, with Card Kingdom’s buylist reaching up to $205. That means they’ve upped their buy price from $170 to $200 to $205 in just a couple weeks—to me this reflects a legitimate rise in demand.

- Another Reserved List card that has shown strength lately is Grim Monolith. While perhaps not at its previous high, the card now appears on Card Kingdom’s hotlist with a $90 buy price. Lightly Played copies start at $105 on TCGPlayer, so relatively speaking Card Kingdom’s buy price is rather aggressive considering that 30% trade-in bonus!

- One very popular Reserved List card is Wheel of Fortune, and it has been a stable card on Card Kingdom’s hotlist for a while now. The buy price has fluctuated some, but currently Card Kingdom is offering $80 for Revised Given its utility in Commander, the red sorcery is likely to climb ever-so-slowly over time as copies disappear into decks, never to hit the market again.