Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

The Modern PPTQ season begins at the end of July. For consummate grinders like myself, this is a call to break out the tech and start polish decks. It's also a call to start playtesting, both to understand how my own deck works and to understand how other decks operate. One of the greatest challenges for a tournament player is facing a deck and having no idea what is happening. Most commonly, this happens against combo decks. Today, I will be explain my strategies for facing combo decks.

It is something of a running joke that nobody understands how Ironworks actually works; not even Matt Nass. That may only be a joke, but Matt did spend a lot of time on camera explaining what was going on to his opponents and (it looked to me) the judges. His primer on the deck is also dense with interactions and lines of play, yet vague about how the combo works. Certainly, Yuri Ramsey didn't seem like he understood what was happening during his finals loss to Matt. This is a huge advantage for any deck, especially combo decks.

The Question of Answers

When it comes to answering combo decks, the first thing that springs to most players' minds is hate. Which is not inaccurate; combo hate is the best way to beat combo. However, what I'm talking about today is when hate is not an option. Perhaps the appropriate hate is normally unplayable, or your deck can't run the right type; more likely, it's game 1, when you won't have any. This is when practice and playtesting are critical. Without the experience and familiarity of playing against the deck, there's no way to know how to win—had Yuri done more playtesting against Ironworks, he might have known the correct time to blow his Oblivion Stone.

However, that may not be possible. The opponent across the table may be living the dream with a completely off-the-wall deck that nobody's seen before. There was no way to prepare for the deck, and now you're completely lost. This is where I've seen a lot of players, myself included, get tilted and give up. It's very dispiriting to be so lost and confused.

However, that may not be possible. The opponent across the table may be living the dream with a completely off-the-wall deck that nobody's seen before. There was no way to prepare for the deck, and now you're completely lost. This is where I've seen a lot of players, myself included, get tilted and give up. It's very dispiriting to be so lost and confused.

The answer is to focus and not panic. Even completely weird decks will have common identifying threads with more mainstream combos that can be seized on. Knowing generally how a combo works provides clues to how to fight back and provide a hope of winning. I may not have the right answers, but as long as I can figure out what is happening, I can determine if I have answers or a strategy that are good enough to win anyway.

Beyond Fairness

I have previously covered the broad categories of combo decks, or the fair and unfair varieties. But whether fair or unfair, combo decks operate in a few predictable ways with some noticeable tells. Reading these tells and knowing what they mean for the combo determines how they can be disrupted.

Critical Mass Combo

Critical mass decks are combo's most recognizable form, i.e. Storm. These decks need certain cards in large quantities to start their combos. They often do nothing for several turns before finding the right cards to win. Once that happens, they "go off" and start doing math to determine a path to victory. Critical mass decks tend give themselves away since they don't do much early but cantrip, sculpt their hands, and maybe play a telegraphing enabler.

There are many options for disrupting critical mass decks. Keeping them off their mass is the obvious move, but that isn't always possible; Storm survives Thoughtseize and Liliana of the Veil via Past in Flames, for instance. A stonewall of counterspells is more effective thanks to instant speed, but not without another element.

There are many options for disrupting critical mass decks. Keeping them off their mass is the obvious move, but that isn't always possible; Storm survives Thoughtseize and Liliana of the Veil via Past in Flames, for instance. A stonewall of counterspells is more effective thanks to instant speed, but not without another element.

The trick is to attack from multiple angles. Jund relies on discard to proactively disrupt Storm, then Scavenging Ooze to close the door. Humans taxes the combo and attacks their hand while presenting a very fast clock. Tron struggles against these combos because Karn Liberated is not very disruptive and its clock is slow. Figure out what kinds of disruption are available and prioritize them.

Snowball Combo

While critical mass decks need their resources before starting to combo, snowball decks build as they go. These decks tend to depend on lots of permanents, and don't hold cards in hand, differentiating them from critical mass decks. Ironworks is a great example. The deck needs certain pieces to combo off, but it doesn't need to have them right away. It can play out its pieces well before actually finding Krark-Clan Ironworks or Scrap Trawler, use them to dig for more cantrips or crucial cards, and just build up over a period of turns to eventually combo off, as does a snowball rolling down a hill.

Ideally, it's best to prevent these types of decks from gaining momentum in the first place. This isn't always possible, as for example Ironworks plays cantrip artifacts to find and fuel its combo. Each Chromatic Star popped is a chance to hit and play another one. It's not really possible to disrupt that chain meaningfully. Focus instead on what the deck is lacking, be that a critical piece, mana sources, or even card quantity, and attack appropriately. The timing of disruption is far more important here than against critical mass.

Ideally, it's best to prevent these types of decks from gaining momentum in the first place. This isn't always possible, as for example Ironworks plays cantrip artifacts to find and fuel its combo. Each Chromatic Star popped is a chance to hit and play another one. It's not really possible to disrupt that chain meaningfully. Focus instead on what the deck is lacking, be that a critical piece, mana sources, or even card quantity, and attack appropriately. The timing of disruption is far more important here than against critical mass.

The goal is to either stall or break the snowball. For example, the current version of Ironworks needs its namesake and Scrap Trawler to win via Pyrite Spellbomb recursion. Once the combo gets going, it will find multiple copies of both. However, if either is removed early, there may not be opportunity to find more. Removing Ironworks in response to Trawler or vice versa breaks the engine. Ironworks without Trawler means mana but no guarantee of more fuel; the opposite means fuel, but no way to use it. If the chain hiccups, it may be difficult to restart, providing a window for opponents to win. Waiting too long looking for value or a more opportune moment lets the snowball grow out of control. Hit the combo at the earliest opportunity.

Right Card Combo

These combos revolve around a small number of cards that win the game if resolved. These combos are self-contained and independent of the rest of the deck. Storm needs the right cards to go off, but it also needs them in quantity. Valakut needs to have its namesake card to win, but doing that doesn't automatically win the game. These two decks require more to happen once the combo is assembled.

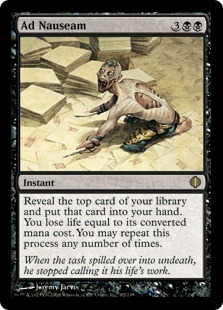

Right card decks include Ad Nauseam and Splinter Twin. If Splinter Twin resolves on a Deceiver Exarch, the combo has succeeded. Nothing else needs to happen; there's no question of resources or possibility of fizzling. The assembled combo wins unless immediately disrupted.

These decks can be the hardest to recognize in-game. They don't build to anything, and may not telegraph the combo at all. A deck like Ad Nauseam is mainly cantrips and artifact mana so it does telegraph, but it's an exception. Fair combo decks like Twin or Abzan Company tend to fall under this category, and to the uninitiated, they do not look like combo decks.

These decks can be the hardest to recognize in-game. They don't build to anything, and may not telegraph the combo at all. A deck like Ad Nauseam is mainly cantrips and artifact mana so it does telegraph, but it's an exception. Fair combo decks like Twin or Abzan Company tend to fall under this category, and to the uninitiated, they do not look like combo decks.

The identification method I use is to ask myself whether the deck is doing something good enough for Modern. If what I'm seeing looks mediocre at best or has odd card choices, I get suspicious and adjust my play so that if there is a combo coming I have an answer.

To defeat these combos, simply prevent the combo from resolving. Unlike the other types of combo, there are no alternative routes to victory. Cards A and C must be resolved with Card B in the right order. Answering any piece of the combo by any means disarms it: Ad Nauseam cannot realistically win without its namesake card; counter or discard the Ad Nauseam, and the deck fizzles. However, the risk is that opponents can simply topdeck another copy of the missing piece and slam it down for the win.

Therefore, these are the only types of decks where Cranial Extraction effects are as good as players think they are, to the point that Ad Nauseam conceding to Slaughter Games is reasonable move. Whether this applies to a specific right card combo depends on the deck. It is completely true of Ad Nauseam, arguable about Ironworks, and completely untrue of Abzan Company and Splinter Twin.

How to Respond

Determining what combo type and how to fight it are only part of the battle. The next step is deciding what your deck can actually do against that combo. This is entirely dependent on what you're playing. The more answers in the deck, the more options available, but that can be a trap. It is critical to identify the best strategy for your deck in the situation.

Quantity of Answers

This option is the classic stonewall approach: just answer everything relevant, and the combo fizzles.  Of course, identifying the relevant spells can prove tricky. On the surface, only Gifts Ungiven and Past in Flames really matter in Storm, but only countering those cards can leave the door open for multiple Grapeshots with Remand.

Of course, identifying the relevant spells can prove tricky. On the surface, only Gifts Ungiven and Past in Flames really matter in Storm, but only countering those cards can leave the door open for multiple Grapeshots with Remand.

The problem with this method is that it isn't sufficient by itself. UW Control can counter as many spells as it wants, but if it doesn't apply pressure, Storm will eventually force its way through. This is why Vendilion Clique is so good against combo decks: it both disrupts and closes out the game.

Tempo them Out

This is the most common method, and the reason that aggro-control and tempo decks are so strong against combo. This strategy uses disruption to slow the combo deck to ensure that its clock is faster. Discarding or countering a few key pieces while creatures crash in is the classic anti-combo strategy for a very good reason. Humans is a prime example of this strategy since its clock is also its disruption. Tempo-ing combo decks doesn't require that much disruption; just the right piece at the right time.

Destroy the Combo

The third method is to proactively destroy the combo, or remove the combo pieces from the combo deck. As previously mentioned, this is most effective against right card decks, but it is also hard to do incidentally. Cranial Extraction and Slaughter Games are not very good cards normally, so there's little reason to have them except as combo hate. Surgical Extraction sees more play, and can do the job, but only if the right piece is in the graveyard and the game isn't lost. Generally, this is only possible if it's intentionally built into the sideboard.

Moot the Combo

Sometimes, a deck simply isn't vulnerable to an undisrupted combo. This is a very rare situation, but it can happen. Mooting a combo doesn't disrupt or prevent the combo, but instead renders it superfluous and unable to actually win the game. The combo still goes off, but it isn't lethal. The best example I have is Soul Sisters vs Splinter Twin. As long as Sisters had a Soul Warden on the battlefield, Twin  could never combo-kill with Deceiver Exarch because every Exarch made was countered by a point of lifegain. Two sisters stopped Pestermite.

could never combo-kill with Deceiver Exarch because every Exarch made was countered by a point of lifegain. Two sisters stopped Pestermite.

This is not playing Platinum Angel. Angel functions more like a hate card, since it prevents the effects of the combo (theoretically). To moot the combo, it must be rendered impotent without a direct attack or roadblock. The only way I know for this to work is through lifegain. Lots, and LOTS of lifegain. Creature combo is pretty rare these days, so the only way I can think of to gain inordinate amounts of life is Martyr of Sands. Even then, it takes multiples, and probably recursion to really be out of Storm or Valakut's reach.

Just Race

Some decks just don't have the means to realistically disrupt a combo. Their only hope is to race. Just because the combo deck can goldfish on turn three doesn't mean it actually will. Every tournament-caliber deck has a failure rate. The more pieces required to win, the more likely it is to fail. Many combo decks can't really win playing normal  Magic, and therefore tend to have higher failure rates than non-combo decks. That rate increases the more pressure is applied. Putting the combo deck on the clock and forcing them to win first may yield a win.

Magic, and therefore tend to have higher failure rates than non-combo decks. That rate increases the more pressure is applied. Putting the combo deck on the clock and forcing them to win first may yield a win.

Linear aggro decks have historically bad matchups against combo because they don't interact, but aggro decks also have low failure rates. They're more likely than other decks to actually hit their goldfish target in a given game (usually turn four). Therefore, forcing a combo deck to go off or die before they're actually ready is a perfectly valid strategy. It's not ideal, but if your deck lacks the means to disrupt the combo, leaving them dead on board and crossing your fingers can work.

Don't Play Scared

Never underestimate the ability of combo players to not "have it." Combos do fail of their own accord. I frequently see newer players playing so scared against combo decks that they fail to win games. Rather than simply playing their strategy and trying to win, there is an obsession with representing answers in hopes that it keeps the combo player from going for the win. This can work, but only when the opponent has reason to believe you actually have the represented answer. Even then, given enough time, the combo player will simply sculpt their hand until the represented answer is irrelevant.

While in interactive matchups it is often correct to play around cards, that isn't always possible against combo. Against a decent combo player, it will actually hurt more to play around them than to ignore them. The combo player will go for it at some point, and the later that point is, the more likely the combo is to succeed. Disrupt the combo or race the combo; just don't try and bluff the combo if it impedes your own gameplan. Make your opponent as afraid of your gameplan as you are of theirs, and even against completely unknown decks, you stand a chance of victory.

While in interactive matchups it is often correct to play around cards, that isn't always possible against combo. Against a decent combo player, it will actually hurt more to play around them than to ignore them. The combo player will go for it at some point, and the later that point is, the more likely the combo is to succeed. Disrupt the combo or race the combo; just don't try and bluff the combo if it impedes your own gameplan. Make your opponent as afraid of your gameplan as you are of theirs, and even against completely unknown decks, you stand a chance of victory.

Just logged in to say I appreciated this article a lot. Quality content here, and very complete as well.

Nice article. I think it warrants further musings, even.

Recently I watched Matt Nass play against an opponent in a top 8 match. It may even have been a final.

What I saw baffled me. His Tron opponent had an oblivion stone on the battlefield. He had the mana to activate it. Matt took his turn and the first few things he did (spells, abilities etc) he deliberately paused and gave his opponent credit for knowing when to crack the o-stone and disrupt the combo. His opponent did nothing. Matt kind of physically stuttered a couple of times, in surprise I guess, as he was allowed to just enact the combo and build an unassailable position.

By the time his opponent decided to crack the o-stone it was too late and didn’t do anything at all. At the highest level of play in the finals of one of the biggest tournaments on the planet, Nass’ opponent made what looked like an FNM-level rookie error.

I backed up the footage and watched it a couple of times, too. I wanted to watch it from the Tron player’s perspective and see if I missed anything. Nope. I’m flummoxed haha. There was a definite clear moment where cracking the o-stone denies Nass the ability to go off that turn, but i guess the Tron player just wasn’t familiar with the deck or was exhausted from a day of playing. Either way, with the removal on-board and the mana to use it, he just handed Nass the game. It was a little strange to watch but then I had to check myself because just like that Tron player, I’ve made similar errors in my time and all of them are circumstantial and forgivable.

Still. I thought it was worth mentioning.

That was the finals of GP Las Vegas, and it’s the moment I was referencing. Matt clearly knew that he couldn’t actually go off that turn and was setting up to make Yuri pop the Stone so he could potentially go off later, and Yuri did nothing. He clearly didn’t understand what was happening and didn’t read Matt’s pauses as cluing him in. Whether Yuri could have won the match is another matter, but he definitely shouldn’t have lost that turn.

In fairness to Yuri, it was the finals of a GP. Exhaustion and the pressure of being under the lights were certainly factors and may be the real explanation. However, I’ve seen the exact same thing at local events.

hello! i loved the article. i am trying to learn KCI myself, and i don’t really understand what happened when matt got up to ask the judges about overpaying for a spell with colored mana. there were a few things that puzzled me:

1) he never played a natures claim (i expect that’s what he was overpaying for)

2) paying to cast a spell is a mana ability and cannot be responded to, so couldn’t he have just gotten all the triggers on the stack while “overpaying” for the colored spell and just won on the spot?!

3) or did he just end up not having to do that at all and thats why i didn’t see him even play a natures claim?

4) (unrelated to the gp) in matt’s primer, in the side boarding plans there were a lot of times where he sided out all the myr retrievers. isn’t it impossible to do the draw your deck and make a lot of mana loop without the myr retriever?!

an answer would be greatly appreciated! 🙂

and also any tips for playing kci as well 🙂

thanks!

Not an expert by any stretch, but I *think* that Matt was trying some tricky play where he’d announce his spell, presumably Nature’s Claim, then crack a number of Chromatics as mana abilities to pay for it. Normally you tap mana then play a spell, but you can also announce the spell then pay, but there’s really no reason to do one over the other.

The problem is that you cannot “overpay” for a spell. You must pay the exact cost, that being CMC +/- any taxes or reduction effects, and can’t pay more. You can float as much mana as you like, but any mana that is unused for the spell just sits in your mana pool. For a spell with X in the cost you still don’t overpay for the spell, you just pay the cost and however much X you want. I don’t have any idea what Matt was thinking or any idea why he wanted to try it, and I couldn’t find a good explanation anywhere. You are right, he didn’t need to go through that judge call and could have just won.

Post sideboard the most common hate players have for KCI is graveyard hate. My understanding is that KCI reduces its reliance on the graveyard and the Retriever loop to compensate.

KCI is a very complicated deck, the only advice I have is practice until it’s rote memory, and even then don’t assume you know everything that could happen.