Are you a Quiet Speculation member?

If not, now is a perfect time to join up! Our powerful tools, breaking-news analysis, and exclusive Discord channel will make sure you stay up to date and ahead of the curve.

The London mulligan has been with us now for four months, and players are speaking up on what they think of it. As a lover of the London mulligan and of mulligans in general, I've followed this topic with particular interest. One piece that recently caught my attention was Zvi Mowshowitz's article "Ban the London Mulligan" from earlier this week (guess how he feels about the rules change!). Zvi's sentiments reflect different arguments I've heard from players since the rule was first suggested by Wizards.

While Zvi's article was written chiefly with Standard in mind, he mentions that his arguments hold for constructed play generally. Today, I'll address his concerns one-by-one and reveal the degree to which I think they do or don't apply to Modern.

The Theory of Messed-Up Relativity

Early on in his piece, Zvi establishes the power dynamic at work between cards of differing quality.

Early on in his piece, Zvi establishes the power dynamic at work between cards of differing quality.

You are not going to succeed in Standard, for a long time, no matter what is banned, without building around at least one messed up [sic] Magic card from Throne of Eldraine. If design does not make large adjustments, and likely even if they do, every good Standard deck for a long time is going to have a key messed up Magic card.

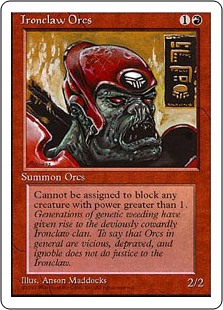

"Messed-up" is a stand-in for "broken," "busted," "warping," or any preferred buzzword. I find that such terminology can be useful so long as it's clearly defined; otherwise, it remains a buzzword. One aspect these words all share: they cannot exist without context (or, to use another buzzy phrase, "in a vacuum"). Even "good" and "bad" cards are only so because of their power relative to the other options. For instance, if every creature was a two-mana 1/1, the first-ever one-mana 1/1 would indeed be broken. There was indeed a time in Magic's history when Ironclaw Orcs was to Sligh decks what Goblin Guide is now.

"Messed-Up" as Goodstuff

In this case, the adjective "messed-up" is applied to the noun "cards." So we're not only talking about powerful things happening, but powerful things happening by virtue of a single card resolving or being drawn. In Magic lingo, we can summarize this concept as "goodstuff," the alternative being "synergy" (or when multiple cards come together to yield a powerful effect).

In this case, the adjective "messed-up" is applied to the noun "cards." So we're not only talking about powerful things happening, but powerful things happening by virtue of a single card resolving or being drawn. In Magic lingo, we can summarize this concept as "goodstuff," the alternative being "synergy" (or when multiple cards come together to yield a powerful effect).

Modern used to be more goodstuff-oriented than it is currently. For a time, players were sleeving up Tarmogoyf or Lightning Bolt or just losing; the cards were better than everything else by a degree that invalidated most strategies trying to string together some other gameplan. Now, things have changed. In one sense, the arrival of Fatal Push both drastically decreased Goyf's relative strength and diversified playable removal options. But more pertinently, Modern's rich card pool has benefited from recent printings; the format's available synergies are now far stronger than the individual power level of its most "messed-up" cards.

"Messed-Up" as Synergy

Another interpretation of the term does away with the notion of cards holding their own independently. When it comes to synergy, we're working with enablers and payoffs. A "messed-up" card could very well be an extremely efficient enabler (in Modern's case, something like Faithless Looting), or payoff (think Urza, Lord High Artificer).

Another interpretation of the term does away with the notion of cards holding their own independently. When it comes to synergy, we're working with enablers and payoffs. A "messed-up" card could very well be an extremely efficient enabler (in Modern's case, something like Faithless Looting), or payoff (think Urza, Lord High Artificer).

Zvi seems to grasp this concept:

Even more than a single messed up Magic card, these decks have central play patterns.

A goodstuff deck, like Jund, is content to slam whatever individually powerful cards it draws and hope they're good enough. But the more a deck trends towards the synergy end of the spectrum, the more it becomes reliant on central play patterns. Such patterns can be as explicit as assembling a two-card combo (e.g. Sword of the Meek and Thopter Foundry) or as mundane as curving out properly (e.g. Gilded Goose into Oko, Thief of Crowns).

One Game? I'll Show You One Game!

Put another way, I detect a tension between Zvi's railing against "messed-up cards" and his identification of powerful synergies as driving players to mulligan so much. It seems that goodstuff cards are the fall guy here; it's the allure of synergy that keeps players going back for new hands. And his thesis is that the London mulligan makes those powerful synergies too consistent.

Every game looks the same. Both players do their thing, or else one player fails to do it, is likely also down cards, and never has a chance. Lots of time is spent shuffling, and going through the same motions over and over again.

"Looks the same" is—you guessed it!—relative. But in any case, the more consistent the game gets, the more alike games come to look. This particular complaint is one often leveraged against Yu-Gi-Oh!, a manaless game I've written about before that's leaps and bounds more consistent than Magic. There, extremely lenient combo requirements (or in brickier decks, one-card starters) all but ensure that players successfully "do their thing" on turn one, leaving it up to opponents to "break the board." And since that board-breaking card may well be sitting on top of the deck, pilots can't really concede to their opponents, since they technically have a chance to win. They're forced to sit through 5-10 minutes of enemy combos before checking to see if they can clear the field of what are basically walking counterspells and do their own thing.

"Looks the same" is—you guessed it!—relative. But in any case, the more consistent the game gets, the more alike games come to look. This particular complaint is one often leveraged against Yu-Gi-Oh!, a manaless game I've written about before that's leaps and bounds more consistent than Magic. There, extremely lenient combo requirements (or in brickier decks, one-card starters) all but ensure that players successfully "do their thing" on turn one, leaving it up to opponents to "break the board." And since that board-breaking card may well be sitting on top of the deck, pilots can't really concede to their opponents, since they technically have a chance to win. They're forced to sit through 5-10 minutes of enemy combos before checking to see if they can clear the field of what are basically walking counterspells and do their own thing.

That description may sound horrible to you, in which case I'd advise against ever playing Yu-Gi-Oh! But it's fine with the game's many players, including myself. And Magic, even with the London mulligan, is much, much less consistent than Yu-Gi-Oh!

My experience playing that game has taught me that such happenings are due to not individually powerful cards, but synergy. Whenever Yu-Gi-Oh! bans a combo starter, other, slightly-less-efficient ones take its place; if payoffs are banned, other, slightly-less-impactful ones rear their heads.

My experience playing that game has taught me that such happenings are due to not individually powerful cards, but synergy. Whenever Yu-Gi-Oh! bans a combo starter, other, slightly-less-efficient ones take its place; if payoffs are banned, other, slightly-less-impactful ones rear their heads.

Death of the (Planned) Plan B

When a deck fails to assemble its core components in the right way, and therefore to execute its key play pattern, it falls back on a secondary path to victory, or "Plan B." That plan can be as cohesive as going wide with 3/3 Elks or as strung-together as beating down with an exalted Birds of Paradise. Zvi seems to be lamenting the loss of the former, more deliberate Plan B that occurs when a game becomes more consistent; as he notes, there's little reason to invest precious deckbuilding space in a Plan B when the Plan A comes together so reliably, which then makes the deck more anemic in the rare instances that it doesn't.

Magic is great because it continuously presents unique situations to its players. Decks and players are forced to be flexible and roll with the punches, to plan for not having access to their key cards. When instead decks and players are rewarded for relying on their central repetitive play patterns, because fallback sequences would lose anyway, Magic loses much of its appeal.

Although I can't speak for Standard, I'd argue that Plan Bs are actually alive and well in Modern. That's one reason Oko has enjoyed so much popularity here, even in decks where he just barely contributes to the Plan A—he offers players novel angles of attack, an attractive option in a world with hate cards so efficient that Modern players expect to be disrupted. Here, leaning too heavily on one gameplan is asking for trouble, as opponents are well-versed in how to disrupt linear strategies. "So Wrong It's Right: Accepting Tension" covers this idea in depth, suggesting that Modern players have much to gain from diversifying their strategy.

Although I can't speak for Standard, I'd argue that Plan Bs are actually alive and well in Modern. That's one reason Oko has enjoyed so much popularity here, even in decks where he just barely contributes to the Plan A—he offers players novel angles of attack, an attractive option in a world with hate cards so efficient that Modern players expect to be disrupted. Here, leaning too heavily on one gameplan is asking for trouble, as opponents are well-versed in how to disrupt linear strategies. "So Wrong It's Right: Accepting Tension" covers this idea in depth, suggesting that Modern players have much to gain from diversifying their strategy.

If anything, the London mulligan contributes to that line of defense. Players can run fewer copies of each hoser, and therefore a more diverse array of bullets, with the understanding that they can better find those cards at the beginning of a game. Granted, if the hoser in question doesn't exist in a certain format (as in Standard), all that falls apart.

Living in the Past

The "theory of messed-up relativity" fleshed out above also applies to synergy, the now-established culprit behind excessive mulliganing.

Thus, the first player is forced to mulligan hands that look perfectly good, but which cannot pull off their key play pattern.

If everyone is pulling off their key plays with greater consistency, a hand that cannot do so is, relative to most other hands, bad. So why does this bad hand "look perfectly good?" Perhaps because it contains a payoff or an enabler, and either of those may be perceived as "messed-up" based on how efficient they are in that role relative to other cards legal in the format. But as we've touched on, opening one of those cards doesn't guarantee victory; decks must combine both payoffs and enablers to successfully assemble synergy.

If everyone is pulling off their key plays with greater consistency, a hand that cannot do so is, relative to most other hands, bad. So why does this bad hand "look perfectly good?" Perhaps because it contains a payoff or an enabler, and either of those may be perceived as "messed-up" based on how efficient they are in that role relative to other cards legal in the format. But as we've touched on, opening one of those cards doesn't guarantee victory; decks must combine both payoffs and enablers to successfully assemble synergy.

While it's theoretically possible that Zvi wants to keep every awful hand featuring Oko and feels bitter about shipping them back, I think a more realistic assessment is that the hands he's describing fulfill now-outdated requirements of playability, i.e. they contain "lands and spells." In contemporary Magic, though, those hands aren't good enough. If they "look perfectly good," maybe we just need more practice; losing with those hands enough times should teach us, brute-force style, that our perception is skewed. Identifying when a "good-looking hand" will actually win us the game has been a cornerstone of mulligan decisions since the system was invented, and while the London changes the parameters of what constitutes a good hand, it doesn't change the fact that mulligans are about doing that kind of assessment.

A Question of Taste

Which brings us to the agenda on the table. Why should a hand that may be fine by antiquated standards, but unplayable by current standards, need to work now? As I see it, Zvi's argument is akin to expecting Modern Red Deck Wins decks to run Ironclaw Orcs. Naturally, they can't, as there are much stronger options. But does that mean Wizards has mismanaged the game, or simply drive home that outdated standards don't necessarily apply past their expiration date? That question is for every player to answer for themselves, the reason being that as power cannot exist in a vacuum, taste cannot be universalized. It's personal.

Which brings us to the agenda on the table. Why should a hand that may be fine by antiquated standards, but unplayable by current standards, need to work now? As I see it, Zvi's argument is akin to expecting Modern Red Deck Wins decks to run Ironclaw Orcs. Naturally, they can't, as there are much stronger options. But does that mean Wizards has mismanaged the game, or simply drive home that outdated standards don't necessarily apply past their expiration date? That question is for every player to answer for themselves, the reason being that as power cannot exist in a vacuum, taste cannot be universalized. It's personal.

Let's review the points laid out and dissected with Modern in mind.

- London increases reliance on messed-up cards: FICTION. It increases the reliability of synergy-based deckbuilding, which leads more players to build and play with those synergies in mind.

- Every game looks the same: FACT, in that games look more similar to each other now than they did pre-London, since everyone is doing their respective thing more often.

- Plan Bs are dead: FICTION, at least in Modern. The hate cards are just too strong and prevalent for decks to go all-in on one strategy unless they're broken in their own rite (think Hogaak). This issue has less to do with the London mulligan and more to do with which disruptive cards are legal in a different format.

- We have to mulligan hands that we shouldn't have to mulligan: FICTION. We have to learn to mulligan effectively under the new system, and refine our impressions of what constitutes a keepable hand, as players have done since the mulligan's introduction to Magic.

With the logic parsed, Zvi's only Modern-relevant argument for banning the London Mulligan is the same as the one for keeping Preordain out of the format: it adds too much consistency to the game for his tastes. As a lover of consistency in Magic (to the extent that I ran Serum Powder in my GP Detroit Eldrazi deck) and longtime advocate for freeing Preordain, I feel the opposite way, and quite like what the London has done for Modern deckbuilding. As I understand it, whether you are for or against the London at this point depends on your preferences in Magic, which I'm all about players developing.

With the logic parsed, Zvi's only Modern-relevant argument for banning the London Mulligan is the same as the one for keeping Preordain out of the format: it adds too much consistency to the game for his tastes. As a lover of consistency in Magic (to the extent that I ran Serum Powder in my GP Detroit Eldrazi deck) and longtime advocate for freeing Preordain, I feel the opposite way, and quite like what the London has done for Modern deckbuilding. As I understand it, whether you are for or against the London at this point depends on your preferences in Magic, which I'm all about players developing.

So how consistent do you like your games? Which effects of the mulligan do you most relish or resent? Let me know in the comments!

Happy Birthday!

Couldn’t go an article without mentioning serum powder could you? 🙂

Every rose has its thorn…

Interesting thoughts.

I agree that we’ve gone from ‘the best card is a generic good card in isolation like Lightning Bolt or Tarmogyf’ to ‘the best card requires better supports to do its thing’ but the thing that a Modern player might not appreciate is that in Standard the support tends to mostly be ‘cast this spell on the earliest turn possible’ with reasonable follow-up. So the ‘play pattern’ of Nissa is “Turn 3” and the ‘play pattern’ of Oko is “Turn 2” and so forth. Details matter beyond that but they also… kind of often don’t?

In turn, this is because (and you’re fair to call me out for using a vague term ‘messed up’) the modern card designs are ‘if this card costs 3-5 mana it should take over the game on its own with continuous card advantage or other big thing right away’ as opposed to being a generically good-stuff style thing.

But I do think the central argument against London applies even more so to Modern – when I say that you can’t keep ‘perfectly good’ hands I mean literally any hand that doesn’t do the especially powerful thing that gets you to your destination on the correct turn. Yes, throwing such hands back a lot was *already* good advice! But now it gets pretty extreme, etc etc.

Hi Zvi, thanks for commenting! You’re right, the playability parameters are far stricter in Modern. As for acceptable hands, it seems like we agree: a kept X-carder under London is going to be stronger on average than one kept under the old rules. I’ve really enjoyed testing the limits of what’s possible under the London, for instance in Colorless Eldrazi Stompy and GRx Moon shells.